From oak to vanilla, leather to tobacco, the wealth of flavours found in a glass of whiskey are quite extraordinary. And how these flavours are imparted is nothing less than alchemical. But how can you appreciate those flavours more in your evening tipple? Discover how you can perfect your palate, making your favourite whiskey both enjoyable and informative!

Oak, vanilla, marzipan, honey, leather, incense, tobacco, tar. What could all of these things possibly have in common? Well, each and every one is a common tasting note used to identify whiskey flavours. And we haven’t even started talking about herbs or fruits, yet.

Before we dive into our discussion, let’s be clear about what we mean when we’re talking about the types of whiskey flavours.

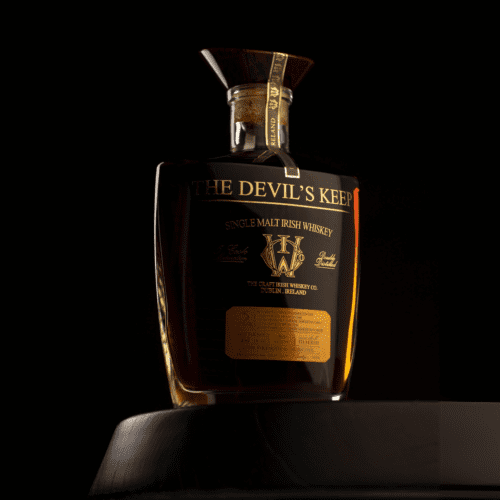

To be sure, none of the aforementioned descriptors are actually inside the liquid. In fact, if we’re talking about formally defined liquids such as Bourbon, Irish Whiskey, and Scotch—they can’t be: You’re not allowed to use any additives in these products. So all of these tasting notes are owed to the casks used to age them. If we’re talking about Straight Bourbon, it’s a mandatory minimum of two years in those wooden vessels. For Irish and Scotch, it’s three years in a whiskey cask. And wood accounts for anywhere between 60-80% of the overall flavour found in your favourite whiskey. The precise number fluctuates with the style.

Remember, when the grain spirit rolls off the still, it always comes out a clear liquid. Elements of the constituent grain (corn, rye, barley—sometimes other cereals such as wheat, oats) can certainly be appreciated if you were to sample it at this point. Indeed, some producers opt to bottle it at this point—a category known as “white dog” in the US or poitín in Ireland. But it carries nowhere near the complexity that it will soon amass after slumbering in the whiskey barrel.

Ageing whiskey is most assuredly not an overnight process. Nor is it a cheap one. Whiskey makers need to patiently wait for years as their initial distillate mellows out in warehouses. More than simply whiskey storage, taking this time allows it to extract all sorts of sensational whiskey cask wood sugars and other assorted flavour molecules from the surrounding staves.

Types of whiskey flavours

To help better identify the specific tastes that develop, certain members of the spirits trade have endeavoured to create flavour wheels. They help us to compartmentalise what we’re experiencing and liken these assorted components to certain things that we’re all familiar with. And when you can see it all broken down in visual form, it’s even more helpful—especially as you’re beginning your journey into the wide, and sometimes overwhelming world of whiskey.

A common example will use up to a dozen generic flavour basics, including sweet, spicy, nutty, herbaceous, floral, fruity, peaty, oaky. Then each of these will be further refined to include myriad examples within each category. Floral could include lavender, rose, and heather. Fruity could mean orchard fruit – apples, pears – and tropical fruit – mango, papaya, pineapple.

Sometimes there’s a very good reason for these analogues. Maybe you taste some banana notes in your favourite Tennessee Whiskey, for example. Well, there’s a good chance that during fermentation, a specific ester—or flavour compound—called isoamyl acetate was formed. And guess what, that’s the very same ester found in a ripened banana! But we’ll go deeper into the science later.

For now, just think about what types of whiskey flavours you’re tasting and how you can take basic inventory as you sip. The best part is, there is no right or wrong answer! Just enjoy your dram of whiskey and see what you find. They don’t even have to be food products at all. Iodine, pine, hay, wet horse?! No matter what it is, you’ll soon learn that calling out any adjective that comes to mind can be one of the best parts of sampling new whiskies.

Discover the different flavours

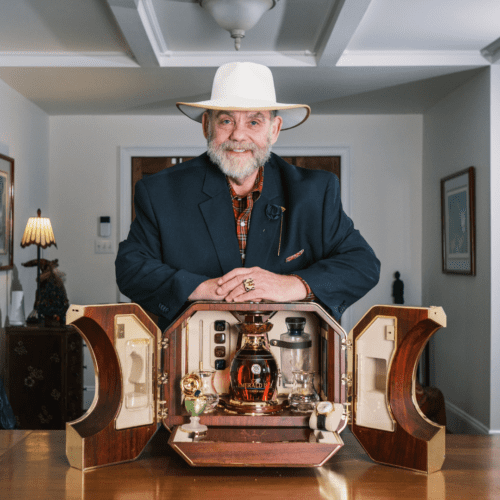

Let’s try a little exercise. To get started let’s look at some of the more popular categories out there, whether it be Scotch, Tennessee Whiskey, Irish Whiskey – even poitín. Choose any one that suits your fancy and have a pen and paper at the ready to take some notes. Now think about what you like about your personal favourites within the selected category. Take some time to sit with the spirit and really think about the specifics of what makes this your personal favourite whiskey. Whatever comes to mind first, just start jotting down these thoughts. Start compartmentalising the whiskey flavours that really stand out.

Move on to another type of whiskey, ideally one within an entirely different category. Again, take careful notes about what it is that you’re tasting. What does it remind you of? Is it sweet, salty, bitter, sour? You can easily find tools to help you with this identification process. If you go online and search for whiskey flavour wheels, you can find dozens upon dozens of descriptors carefully arranged across all spectrum of taste. What you’re trying to do here is to narrow down the focus of what exactly excites you in your preferred whiskeys so that you can hope to seek out similar flavours when you’re exploring new bottlings.

Just like any other skill, you have to keep exercising in order to develop the muscles necessary to succeed. The good news for developing your flavour profile is that this simply requires more drinking. After you’ve compiled notes on all of your go-to whiskeys, you’ll want to look back at everything you’ve written and you should start to see definite patterns emerging.

It turns out that what you like in one whiskey will be quite similar to the same tonalities that you like in others. This might be attributed to the grain used in the whiskey, say corn or wheat or rye if you’re into American whiskey, or malted barley if you’re into single malts. Or even more likely, it is a result of the type of whiskey cask wood used during maturation of the spirit. Remember we said that 60-80% of overall flavour can come from the barrel. So it’s by no means an incidental consideration. If you like a light, tropical topnote; coconut, vanilla, peaches, pineapple, you’re probably more of a fan of American oak. If you find yourself highlighting notes like dates, raisins, sultanas, Christmas Cake, these rich, darker notes are emblematic of European oak–especially an oak whiskey barrel which once held sherry in the southwest of Spain. And then there’s also red berry fruits–strawberries, raspberries–that tend to come from European oak barrels which formerly held red wines or fortified wines from Portugal, France, or Italy.

Whiskey makers utilise all sorts of tools to develop flavours in your favourite dram of whiskey. And the better we triangulate our own palates, the better equipped we will be in order to appreciate their craft.

Adding water to your whiskey

When you’re ready to get a little more delicate and deliberate with your tasting exercises, we recommend procuring some mineral water and a pipette to start administering small drops of it into your favourite whiskey. Literally do this one drop at a time, because the goal here is not to water down your whiskey. The goal is to open up some of those flavour molecules which exist within the dram. Drop it in slowly enough and you should see a slight separation occur in the glass, the oils coming out of solution. Don’t worry. That’s the good stuff. When it separates like that it often means that your whiskey was not chill-filtered, meaning the whiskey maker took careful steps to make sure that nothing was taken out of their product after the ageing process. By freeing up these oils you should get an even more intimate glimpse of the liquid at hand, from the aromas to the taste. Now go back and look at your initial notes and see how your descriptors have evolved as the liquid has “opened up.” This is the world of whiskey, and a glorious one it is too!